http://www.nytimes.com/2011/04/07/opinion/07alexander.html

The New York Times published an op-ed piece by Caroline Alexander, author of The War That Killed Achilles: The True Story of Homer’s ‘Iliad’ and the Trojan War, about the unfortunate misuse of a quotation from the Aeneid. Going beyond a general sentiment that we should know where our quotes (ancient or otherwise) come from, the piece touches on the importance of recognizing that words are endowed with meaning by the context in which they arise. Here are the key bits, but the whole thing is worth reading:

The New York Times published an op-ed piece by Caroline Alexander, author of The War That Killed Achilles: The True Story of Homer’s ‘Iliad’ and the Trojan War, about the unfortunate misuse of a quotation from the Aeneid. Going beyond a general sentiment that we should know where our quotes (ancient or otherwise) come from, the piece touches on the importance of recognizing that words are endowed with meaning by the context in which they arise. Here are the key bits, but the whole thing is worth reading:

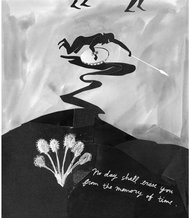

The memorial inscription, “No day shall erase you from the memory of time” is an eloquent translation of the original Latin of “The Aeneid” — “Nulla dies umquam memori vos eximet aevo.”

The impulse to turn to time-hallowed texts, like the classics or the Bible, is itself time-hallowed. In the face of powerful emotions, our own words may seem hollow and inadequate, while the confirmation that people in the past felt as we now feel holds solace. And the language of poets and great thinkers can be in itself ennobling.

But not in this case. Anyone troubling to take even a cursory glance at the quotation’s context will find the choice offers neither instruction nor solace.

…

The immediate context of the quotation is a night ambush of the Rutulian enemy camp by two Trojan warriors, Nisus and Euryalus, whose mutual love is described in terms of classical homoerotic convention and whose deaths represent one of the epic’s famously sentimental set pieces. Falling on the sleeping enemy, the two hack away with their swords, until the ground reeks with “warm black gore.” Stripping the murdered soldiers of their armor, the two are in turn ambushed by a returning Rutulian cavalry troop. As each Trojan tries to save his companion, both are killed, brutally and graphically. At this point the poet steps in to address them directly:

“Fortunati ambo! si quid mea carmina possunt, nulla dies umquam memori vos eximet aevo.”

“Happy pair! If aught my verse avail, no day shall ever blot you from the memory of time.” (The translation here is from the famously literal Loeb edition.) At dawn’s light, the severed heads of the two Trojans are paraded by the enemy on spears.

The central sentiment that the young men were fortunate to die together could, perhaps, at one time have been defended as a suitable commemoration of military dead who fell with their companions. To apply the same sentiment to civilians killed indiscriminately in an act of terrorism, however, is grotesque.

…

The disastrous 9/11 memorial quotation was, evidently, never intended to be more than a high-sounding, stand-alone phrase, never intended to lead visitors to any more profound thoughts or emotions.

Finding words that do justice to a momentous event is always difficult — especially so, perhaps, in the age of Internet trawling, when a wary eye needs to be kept for the bothersome baggage that may be attached to the perfect-sounding expression. There is an easy mechanism, also time-hallowed, for winnowing out what may be right from what is clearly wrong: it’s called reading.

HT Clara Hardy, Sean Cobb, and Will Freiert